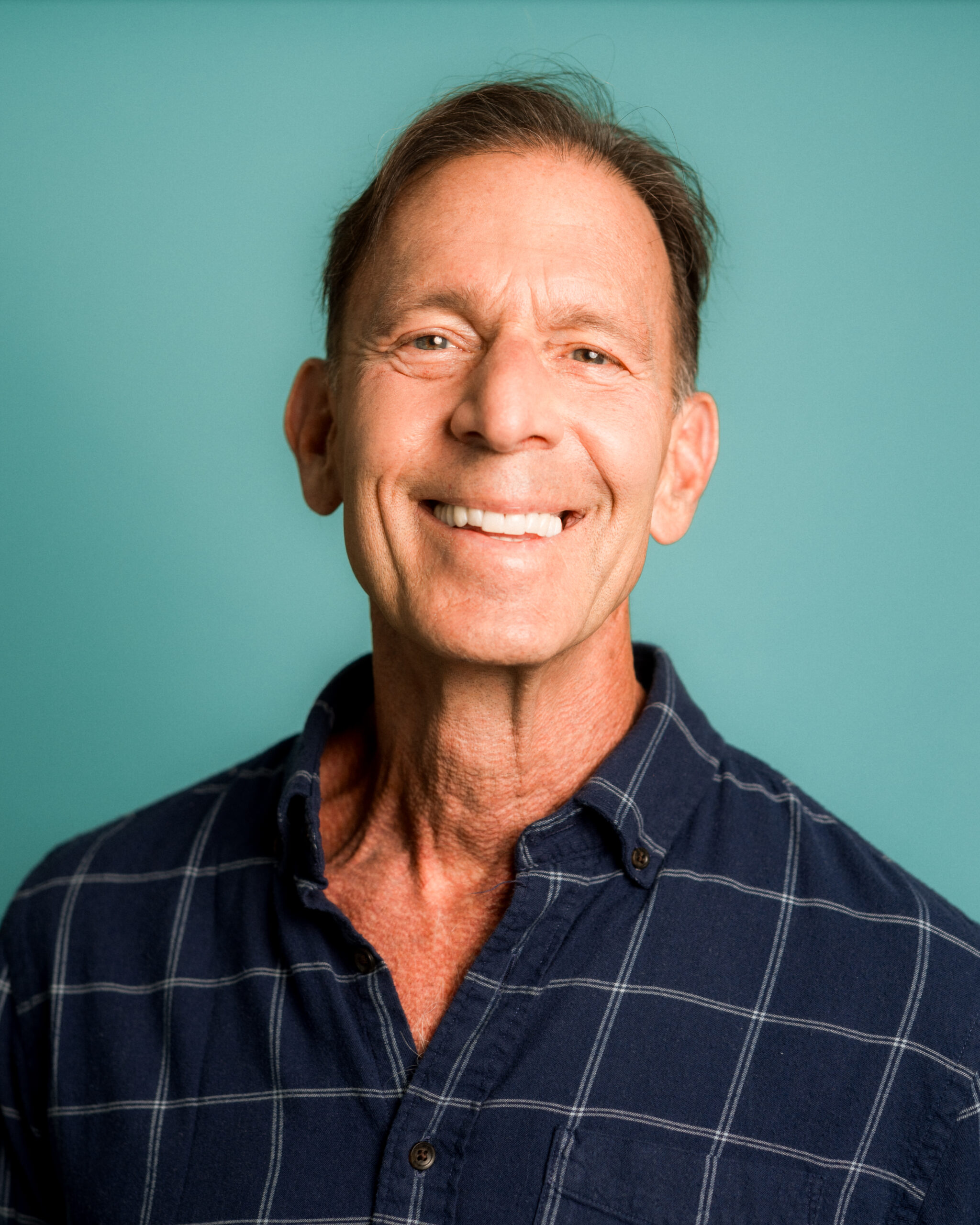

Joseph Deitch is the founder and longtime CEO of Commonwealth Financial Network, which he grew into one of the nation’s largest independent broker-dealers. In 2019, he launched the Elevate Prize Foundation to empower passionate, purpose-driven leaders, activists and innovators.

When Deitch turned to philanthropy, rather than follow a conventional path, selecting a single cause area or setting up your typical perpetuity foundation, he wanted to create a vehicle that could identify and shine a light on high-impact leaders across sectors with the aim of, essentially, creating fandom for social change. The result was the Elevate Prize Foundation, with a mission summed up in its guiding mantra: “Make Good Famous.”

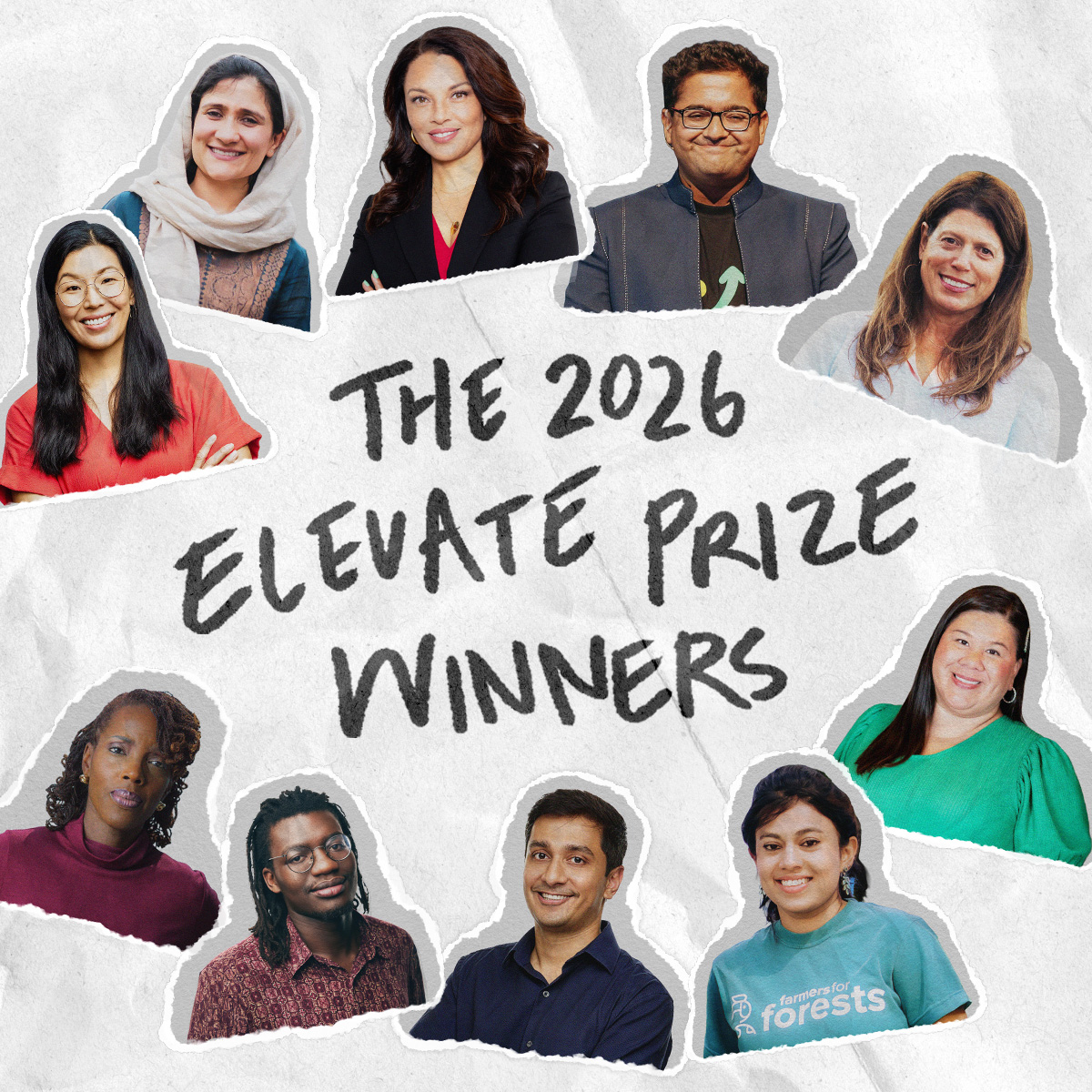

The foundation offers annual, unrestricted awards to social entrepreneurs around the globe, paired with leadership development, media amplification and a robust peer network. Elevate Prize winners come from a wide range of fields, from climate justice to criminal justice reform, united by the foundation’s belief that visibility is as critical to impact as funding.

Some recent Elevate Prize winners include David Flink (2025), founder of The Neurodiversity Alliance, which aims to advance educational equity for neurodiverse learners; Lisa Hunter Romanelli (2025) of The REACH Institute, focused on delivering evidence-based mental healthcare to children and families; and Kwane Stewart (2024), leader of Project Street Vet, which provides veterinary care to pets whose families are experiencing homelessness or housing instability.

In recent conversations with Deitch and Elevate Prize Foundation CEO Carolina García Jayaram, they opened up about what initially drew Deitch into philanthropy, how Elevate’s model sets it apart, and where they see the foundation heading next.

“Let’s give them the ball”: Joseph Deitch’s path to philanthropy

Deitch, now 75, grew up humbly in Massachusetts before attending the University of Pennsylvania and later earning his MBA from Harvard. “We grew up poor,” Deitch said. “I didn’t know I was poor, just, you know, like every other kid there, but, [it was a] poor, blue-collar area in Boston.” He only began to think about philanthropy when he applied to college and started researching grants and scholarships.

Once Deitch started earning serious money, he also started thinking more about inequities in the world and what role he might play in addressing them. “I met with some consultants and they said, ‘You have to pick your vertical.’… I go, ‘I want to make the world better… You’re not the boss of my life,’” he said with a laugh. Deitch aimed to approach giving much like an entrepreneur, leveraging not only money but also his contacts and ideas.

A trip to India with his late wife Robbie Lacritz Deitch in the 1990s also influenced him. They visited what is now known as Mother Teresa’s Kalighat Home for the Dying and later met her at her orphanage. “She said to us — we were all business types — ‘you guys are wonderful’; she was buttering us up. ‘You give people jobs, you give people security. But if you have money in the bank, put it to work some way.’” She hadn’t asked them to give to her directly, he noted, only that they not let resources sit idle.

Deitch recalled the sight of army cots crammed into the stifling hospital, with sick and dying people lying across them. One image stayed with him: “I met this one woman who was skin and bones, and there was a nurse standing next to her, rubbing her arm. I asked her what she was doing and she said Mother Teresa taught us just to love them. We often forget how impactful and how important our love is, our energy is, our intention is.”

Those experiences led Deitch to focus on empowering individuals working on the front lines, leaders who could “get $1 and turn that dollar into $10.” From the outset, the Elevate Prize Foundation was built on that simple thesis: “Let’s look around the world for incredible people who are doing remarkable work. Let’s give them the ball,” he said.

Building the Elevate Prize Foundation and harnessing the power of storytelling

Deitch pointed out that with actors or musicians, the public doesn’t just know about their work, but a lot of other details about their lives. But when it comes to people who aim to make change in the social sector, recognition rarely extends beyond the biggest names like Nelson Mandela or Greta Thunberg.

“On the one hand, these people aren’t looking for fame… but also, in our profit-driven society — and I don’t mean that in a derogatory fashion — there is not a lot of profit in [those stories], so it doesn’t get a lot of attention.”

One of Elevate’s main goals is to raise the profile of social sector changemakers, whether they have a public platform or not.

Each year, the Elevate Prize provides $300,000 to 10 leaders tackling issues like educational equity, access to quality maternal and infant health, and sustainable food, while its monthly GET LOUD Awards deliver $25,000 to grassroots community organizations. Another hallmark of the foundation is the Elevate Prize Catalyst Award, which spotlights cultural icons using their platform for social good. Past honorees include Malala Yousafzai, Michael J. Fox, NBA legend Dwyane Wade and comedian and TV host Trevor Noah, whose South Africa-based education foundation we recently covered.

This year, “Sesame Street” joined that list, receiving $250,000 and recognition for decades of educating and inspiring children worldwide, notable during a time when public TV programming is in the crosshairs. Deitch said that storytelling has served as a way to deliver wisdom from the earliest days of humanity. “You can make your list of 1,000 things to do and 1,000 to not do. And people can’t remember that. At best, we remember, like, two or three things, but stories, we can remember stories…. so the storytelling aspect of this is huge,” Deitch said.

To further deliver on that storytelling prerogative, Elevate Prize Foundation includes a media arm, Elevate Studios, created to amplify the stories of changemakers and bring their work to broader audiences. Through content production, partnerships and campaigns, Elevate Studios helps prize winners and other leaders expand their reach, attract new supporters, and inspire collective action. Elevate’s first studio project is “Nevertheless,” a short-form documentary series on YouTube that highlights extraordinary women who persisted.

Deitch asks us to picture a little girl in Pakistan who fills a pothole. Others notice, and soon members of her community join in, an uncle who’s a contractor, then a neighbor, and so on. Praise itself becomes a reward and the result is what he calls an “upward spiral.”

“We came up with the slogan, make good famous, and that’s a big part of our mission,” he said.

How Elevate works with prize winners

Carolina García Jayaram, now Elevate’s CEO, also spent a month working in that hospital with Mother Teresa. She came to the role at Elevate after a career in arts nonprofits, including as president and CEO of YoungArts. “My background was really in building teams, and I would say, in many ways, pioneering how nonprofits were run and led. That was something I was always very attracted to,” she said.

From the start, Elevate has championed the idea of trust-based philanthropy, but for Deitch, this means intentional trust built on careful research, not blind faith. “When we give them unrestricted funds, it’s because we know who they are… we know what they’ve accomplished, he said.

Elevate is also keen on building community among prize winners and working closely with them in their leadership roles, with a two-year program offering wraparound services and plenty of in-person engagement. Using a cohort model, the program aims to intentionally build a network of leaders across diverse issue areas and geographies, each driving meaningful impact.

One of the most consistent lessons, Deitch said, has been realizing that finding amazing people and giving them money wasn’t enough. Many of Elevate’s winners are visionary leaders, but the foundation provides support in other ways, with assistance in everything from PR and management skills to technology.

In the past year, Elevate deepened that approach by bringing in two specialists, “almost like a fractional CEO, fractional CMO,” Jayaram explained. “It’s very much [about] listening and learning, responding, and then coming in with the tools and resources that can make the most difference to them.”

Celebrity partners like the Elevate Prize Catalyst Award honorees play a role, too, helping Elevate broaden the reach of its winners’ stories. “For celebrities, we’re able to reach much larger audiences through someone like Dwyane Wade or… Malala,” Jayaram added.

What’s the foundation working on going forward?

Down the pike, both Deitch and Jayaram talk about a new initiative, still in its early days, called Elevate Cities, designed to shine a light on hometown heroes at the local level. “How do we drill down into a more hyper-local form of impact? What would that look like?”

Meanwhile, Joe Deitch is expanding his personal philanthropy, a parallel but distinct track from Elevate. He funds cancer research, community health, disaster relief and education, often through ties with the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School. The story here is personal: His late wife passed away from cancer in 2006. Deitch gave a total of $3 million to Dana-Farber to establish the Centers for Early Detection and Interception and to advance the Institute’s Presidential Initiatives Fund. He said he seeks to place the same bets on medical researchers that he does on social entrepreneurs.

“What people don’t realize is that philanthropy is also a very selfish endeavor, not in a bad way. We get to choose areas that speak to us, see what we build, and refine the process in our lifetime. And whatever we put out there comes back to us. If we put out love, it returns multiplied. Doing well by doing good really works,” Deitch said.

This article was originally published on Inside Philanthropy Website.